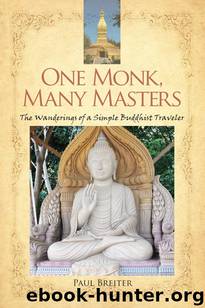

One Monk, Many Masters by Paul Breiter

Author:Paul Breiter [Breiter, Paul]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Cosimo Books

Published: 2012-04-26T07:00:00+00:00

11. Varapanyo’s Last Stand

When you feel like you’re beating your head against the wall, you’ve just got to keep at it until one of them breaks.

—Varapanyo Bhikkhu

Thailand, 1977

The linchpin of Ajahn Chah’s teaching was mai tieng, mai nae: not permanent, not certain. For many years, the thought of disrobing was something I couldn’t relate to at all, like leaving the hospital in mid-surgery. But time flies and everything changes.

And it’s not that I was enamored of the austere bhikkhu life. After five years in robes, my “attainment” was finally feeling that I could hack the lifestyle reasonably well. Some people take to monastic life like fish to water, barely cracking a sweat from ascetic living and staying in robes for decades. I certainly wasn’t one of them. Still, being in robes seemed the only thing to do, and it made a lot of sense. It was hard to conceive of how I would live on the outside.

One result of the training, something that has stayed pretty much intact with me over the years, was being able to distinguish between wants and needs. Buddhist monastic existence is based, physically, on what is called the four requisites: robes to cover and protect the body, almsfood to sustain life, a dwelling to protect against the elements, and medicines to alleviate illness. I explained this to my parents when they came to visit. My mother agreed with the concept, but added that “Some of us just do that in a more elaborate way.”

As a bhikkhu, when I saw laypeople I mostly felt bewilderment. In their way of life, they carried so much that seemed unnecessary and complicating. There was an aura of heaviness about them. I had my own heaviness as well, and a lot of it was silly drama, but I think I was at least aiming in the right direction and not making things more difficult for myself through external involvements.

But everything is subject to change. In 1976, I traveled to the United States with Ajahn Sumedho. In California I saw that there were Buddhist groups studying under authentic teachers and practicing meditation. I stayed a few days with a friend who had a beautiful little cabin on a wooded hillside, and I imagined that lots of people were living that way (not exactly true).

Then came knee surgery and months of limited participation in the daily monastic round. I’d also been laid up with malaria and hepatitis for part of the previous two years, and in the following hot season, just as I was preparing to take a step into bhikkhu adulthood after completing five vassa by going on tudong (an extended ascetic walking tour), I fell ill while in Bangkok.

It turned out not to be anything long lasting or serious, but it dislodged a lot of thinking. I began to wonder if there was more to spiritual practice than enduring physical difficulty. I chewed over Doug Burns’ phrase, “the point of diminishing returns.” For the first time in my Buddhist career, I thought seriously about disrobing.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4786)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4105)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4036)

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan by Jake Adelstein(3997)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid(3829)

Apollo 8 by Jeffrey Kluger(3713)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3642)

Annapurna by Maurice Herzog(3474)

Full Circle by Michael Palin(3452)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(3402)

Kitchen confidential by Anthony Bourdain(3093)

In Patagonia by Bruce Chatwin(2935)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2863)

Finding Gobi by Dion Leonard(2846)

The Ogre by Doug Scott(2686)

Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer(2635)

The Stranger in the Woods by Michael Finkel(2539)

L'Appart by David Lebovitz(2520)

An Odyssey by Daniel Mendelsohn(2309)